Tracking the impact of journalism is a bit like reporting a story. The first facts to establish on the ground are “Who, what, where, when?” — and even that’s not always easy. “How?” and “Why?” take quite a bit more digging, and the deadline pressure is always on. The hardest question to answer at all — Sunday magazine level hard — is “So what?”

Methods for evaluating news were high on the docket at last week’s Online News Association Conference (ONA14), where nearly 2000 journalists gathered to discuss new practices, platforms, and tools.

Many analytics packages are focused on determining reach: who, what, where, when, and sometimes how. For funders, distinguishing how grantees are assessing the impact of news projects is central to understanding the outcomes of their grants. Reach and engagement are important to get, but understanding “Why?” is equally important — and “So What?” is the gold standard of impact, weaving together both qualitative and quantitative elements to reveal the full story of what makes a reporting project worth supporting.

Here are three approaches to the question of analyzing news from conference exhibitors and panelists:

Building data fit for editors

Parse.ly was one of the two large commercial data analytics platforms demonstrating their wares on the Midway—ONA’s exhibition and demo space. Clients include some of the web’s most visible and voluble newsrooms, including FoxNews.com, Mashable, and Slate, plus popular digital-first content providers such as Upworthy and CHEEZburger (engine of countless viral memes).

The Parse.ly suite of tools is designed to help editors work in real time to identify how online audience members are responding to content. Historical data is also available so that editors and marketing staff can compare article and topic performance over time.

Metrics are available for each article, and include traffic, referrals (i.e., what site the user visited previously), and social traction. A “big-board monitor” makes it possible to display trending stories across the entire newsroom. Reporters can also use the platform to engage with users, for example by recommending related stories or thanking them for sharing.

Parse.ly is platform-agnostic — it can be installed across different content management systems, which makes it flexible for use by many different types of outlets. It’s especially valuable for projects that update daily or even hourly, and are willing to conduct multiple A/B tests with headlines, images and formats to see which approaches will yield more visits and responses from readers. Pricing is tiered, based on the number of unique visitors to a site, and all plans include unlimited users, post tracking, and a full reporting suite.

Parse.ly is squarely in the business of providing insights about “who, what, where, when,” specifically online. Based on methods built for bumping ad metrics, it does not include any tools for analyzing how users feel about the content or what they do as a result of having consumed it.

Honing in on attention minutes

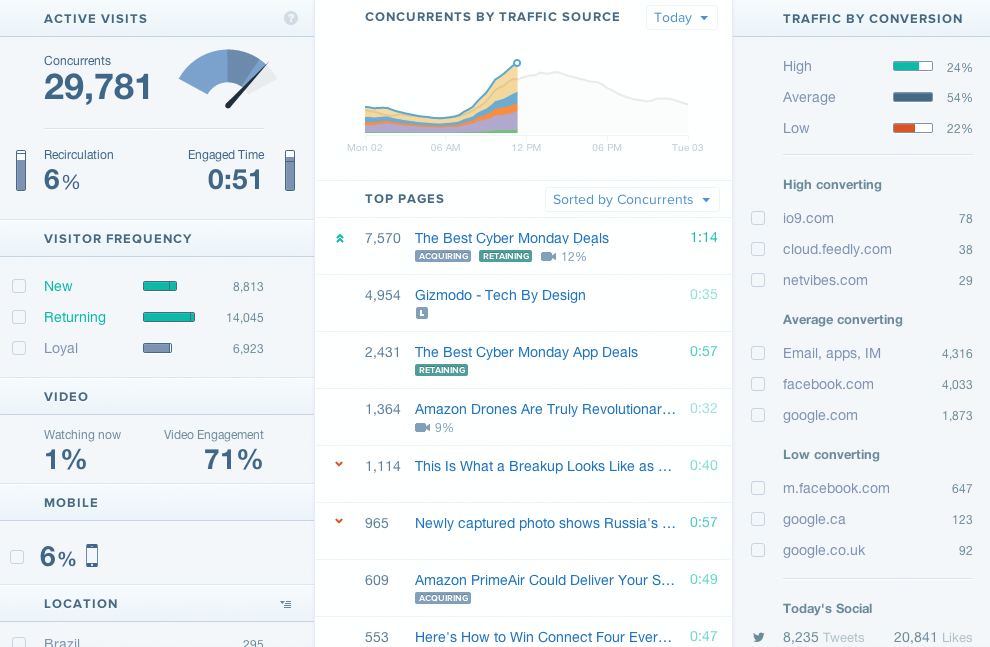

Chartbeat is another large-scale enterprise solution for analyzing real-time audience metrics. Like Parse.ly, the focus is digital, it’s geared for use by both editors and marketing staff, and pricing is based on audience (in this case, concurrent active visitors rather than uniques).

However, while Parse.ly has honed in on news needs, Chartbeat is a general purpose analytics platform with a customized set of services for media and publishing outlets, built in concert with high-profile content creators. Chartbeat’s clients include such heavy hitters as Time, Forbes, Gawker, and NBC Universal, and the dashboard serves up metrics on traffic, platform type, location, referrers, video engagement and more.

Currently, Chartbeat is distinguishing itself by focusing on the concept of the “attention web,” which differentiates tracking content clicks from tracking the amount of time that users spend on content once they’ve clicked. The technology is complicated, but the idea is pretty simple: the longer users spend on a story, the more likely they are to spend more time on the site and become loyal consumers. So, in addition to “who, what, where, when,” Chartbeat wants to elevate the question: “How long?”

Editors and publishers are still grappling with how useful this metric might be. In August, the Media Impact Project (MIP) at USC Annenberg’s Norman Lear Center hosted a debate on this question. At the heart of the dialogue is the issue of how focusing on particular metrics might distort editiorial practice. If a focus on clicks leads to more lowest-common-denominator “clickbait stories” larded with teasers, kittens and side-boob, what will a shift of focus to time spent yield?

ProPublica President Richard J. Tofel asks “do we really want reporters and editors to undertake a constant effort to take up more of a reader’s time, to always lengthen stories where feasible (or at least whenever doing so won’t drive readers away), to use more video simply because people may mindlessly watch? If the business of journalism, to paraphrase Calvin Coolidge, is business, the answer is ‘yes.’ But when it comes to mission-driven journalism (such as the emerging non-profits), substituting a drive for more minutes for, say, a push for change will eventually be corrosive.”

In a rejoinder, Chartbeat CEO Tony Haile argues that mission is not the target: “Tofel is undoubtedly right that trying to understand the impact of a story by quantifying the amount of attention it accrues is wrongheaded. Engaged time can tell you if the story was read, but not if the politician was subsequently convicted or the law overturned. No one metric can universally quantify something as intangible as impact. However that is not the task ahead of us. We are not seeking to understand impact (to misquote the Supreme Court, we may only know it when we see it), but to identify a better currency for exchanging value between advertisers and publishers; one in which advertisers get what they want and where quality content is worth more than clickbait.”

Hacking metrics for mission-driven news

For both funders and mission-driven newsrooms, here’s where the rubber hits the road. Either they can’t afford commercial services such as Parse.ly or Chartbeat, or they have different impact questions — “How?” “Why?” and others — that they’d rather focus on answering. A number of noncommercial newsrooms are also leery of the privacy-invading amount of data it takes to serve up personalized headlines.

Some are taking on this challenge one newsroom at a time. At ONA14, NPR’s Melody Kramer walked attendees through the process of building the NPR Analytics Dashboard, built with advice from Buzzfeed, The New York Times, The Guardian, The Huffington Post, and USA Today. The goal, she says, was to create something useful to the newsroom, so Kramer’s team asked reporters and editors what might make the most sense, and built a related set of “user stories” about how different NPR staff might take an action based on dashboard insights. The team developed the resulting product in six weeks.

Newsroom staff are invited to share their observations at socialmediadesk.tumblr.com. Their primary goal, writes Kramer, was to create “actionable behaviors” based on the dashboard, which newsroom users could then evaluate in a continual feedback loop — with a longer-term outcome of expanding NPR’s core audience. Learn more about their process in this Source piece.

While NPR is aiming to be as open as possible, many smaller mission-focused newsrooms still need more guidance and shared tools. What’s more, there’s a vigorous field-wide debate in progress about whether newsrooms should measure impact at all — and when they do, which outcomes are appropriate.

For smaller newsrooms just getting started with analytics, the Media Impact Project (with support from the Gates, Knight and Open Society Foundations) has begun publishing a series of step-by step guides. In collaboration with the Center for Investigative Reporting, MIP has also been working to sketch out the possibilities, and engage newsrooms in creating an “Offline Impact Indicators Glossary.” This document lays out a range of possible responses to news, from individual engagement (“micro”) to collective response (“meso”) to institutional or “power-holder” level change (“macro”). The taxonomy is explicitly designed to unearth how and why news impact is happening. It also poses a crucial but controversial new question: “What happened next?”

MIP Director Dana Chinn says that she hopes the project can serve as a “safe place” to convene news producers and analysts around impact questions. “I want to identify and validate them,” Chinn says. “My key outcomes are adoption, culture change. I just want to get newsrooms to think.”

Just this week, MIP announced an ambitious new cross-outlet “Media Impact Project Measurement System.” Once in process, it stands to provide answers to that most elusive of questions: “So what?”

As we’ve reported, the question of how best to assess the impact of documentary has reached a critical mass in recent months. Now, it looks as though we’re poised for a round of major debates on the news side. Keep an eye on our Assessing Impact of Media (AIM) page to stay up-to-date.